Opinion by Barrisford Petersen

Preamble

The 16th January 2025 marked 31 years since the start of my career in the oil and gas industry as a contracts officer for a small state owned company called Southern Oil Exploration Corporation, also known as Soekor. One of the many reasons for the establishment of Soekor in the mid-60s was the then government’s response to international economic sanctions against South Africa. Soekor’s budget was understood to be open-ended, with a mandate for finding oil in South Africa at all costs. Soekor was granted two exclusive oil and gas prospecting leases, respectively named OP29 (onshore) and OP26 (offshore). These prospecting leases have now expired.

Numerous discoveries onshore and offshore were made by Soekor, although not all of them were at the time considered commercial. Most prominent was the F-A gas field in the Bredasdorp Basin, situated 85km offshore Mossel Bay. When production commenced in 1992 the gas was piped to an onshore gas-to-liquids (GTL) refinery. This was referred to as the “Mossgas Project”. With offshore gas reserves just short of 1 trillion cubic feet (TCF), at the time, the Mossgas onshore plant was considered the largest gas-to-liquids facility in the world, with a production capacity of 45,000 barrels of oil equivalent (boe) per day.

Subsequent to South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994 and the formation of a new democratic government, sanctions were lifted and the immediate imperative for domestic oil exploration declined. South Africa could freely purchase oil on the international market. Soekor was given a new mandate to transform itself into a self-sustaining commercial entity, not reliant on state funding. In fulfilment of that mandate, Soekor investigated international oil and gas opportunities, sought to bring in joint venture partners to fund exploration, and develop and produce those commercial discoveries already made in South Africa.

Soekor, with partners such as Energy Africa (local) and Pioneer Natural Resources (at the time the largest USA independent oil company), proceeded to develop three commercially successful and internationally recognised offshore oil and gas production projects called Oribi, Oryx and Sable. I was fortunate to be part of all three offshore production projects, providing legal support. During the period 1996 to 2002, Soekor built a phenomenal oil and gas project development team which had a proven and successful track record in offshore oil and gas development projects.

Under a ministerial directive from the then Minister of Minerals and Energy, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Mossgas and Soekor were compelled to merge, forming the national oil company that we now know as PetroSA. Many experts considered the merger unwise and strongly advised against it. Instead of taking one year to merge these entities, it took three years to complete. This was a tumultuous period for many employees, especially many of the seasoned senior executives, at both Soekor and Mossgas. The dreadful manner in which the merger was overseen resulted in many highly experienced oil and gas professionals, responsible for South Africa’s world class successful exploration, development and production projects, leaving and being replaced by individuals with little to no upstream oil and gas exploration and production experience. I resigned as Manager: Legal Services in September 2002 as the working environment had become intolerable: a story that unfortunately has been, and continues to be, repeated in many state owned companies/enterprises.

Today, unfortunately, PetroSA is a figment of its former self, considered by many to be insolvent, noting the Mossgas GTL refinery, its primary income generating activity, being offline for the last four years without any commercially viable gas feedstock. The primary reason therefore, in my opinion, is the failure to properly plan and invest in gas exploration at critical phases. PetroSA is once again the target of yet another merger that was triggered at direction of the Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, Mr Gwede Mantashe in 2021. The merger of PetroSA with other subsidiaries of the Central Energy Fund (CEF) to form the new South African National Petroleum Corporation (SANPC) is, as I understand it, in the final stages of completion; having taken more than five years since originally being announced by the President in the 2020 state of the nation address.

A bit of onshore gas history

That South Africa has onshore gas, is nothing new. It is not as though onshore gas has only recently been discovered in South Africa. Reports filed with the Council of Geoscience (CGS) record 1000’s of boreholes that were drilled onshore South Africa for the purpose of minerals mining and petroleum exploration. Many boreholes drilled for mining operations reportedly encountered gas, coal bed methane (CBM), also called commonly referred to as coal seam gas (CSG). Then, the presence of CBM was considered more of a hindrance and a safety risk.

Because of South Africa’s coal-resource abundance, coal was the chosen commercial solution for power generation in South Africa, with coal-fired power stations that were located alongside coal mines since at least 1923 when Eskom, as we know it now, was established. Onshore CBM was all but ignored and considered commercially uneconomic when compared to coal for cheap power generation. How the world has changed since then, with the focus aggressively shifting to clean energy solutions.

It was not until 2011 when Australian Stock Exchange (ASX)-listed Kinetiko Energy Limited (Kinetiko/KKO) stimulated renewed international interest and investment in South Africa’s onshore gas potential by farming into 1800 km2 of potential gas-bearing acreage in the Amersfoort area of Mpumalanga. Kinetiko has, since then, drilled more than forty (>40) onshore boreholes with a close to 100% success rate in encountering gas. Over the years, many challenges, as a first mover, were successfully handled by Kinetiko; however, at the expense of time. Kinetiko has since expanded its acreage position to more than 6000 km2 with approximately 11 TCF of independently certified prospective and contingent gas resources; potentially ten times the size on which the Mossgas project was based without the complexity of being offshore. What is not appreciated is that 11 TCF of gas is the equivalent of discovering a 1,870 billion barrel oil field in the heart of South Africa and, if fully funded and developed, has the potential to power nine 1GW power stations for 20 years. Kinetiko is currently establishing a pilot gas to power development project that has the potential to expand up to 500MW.

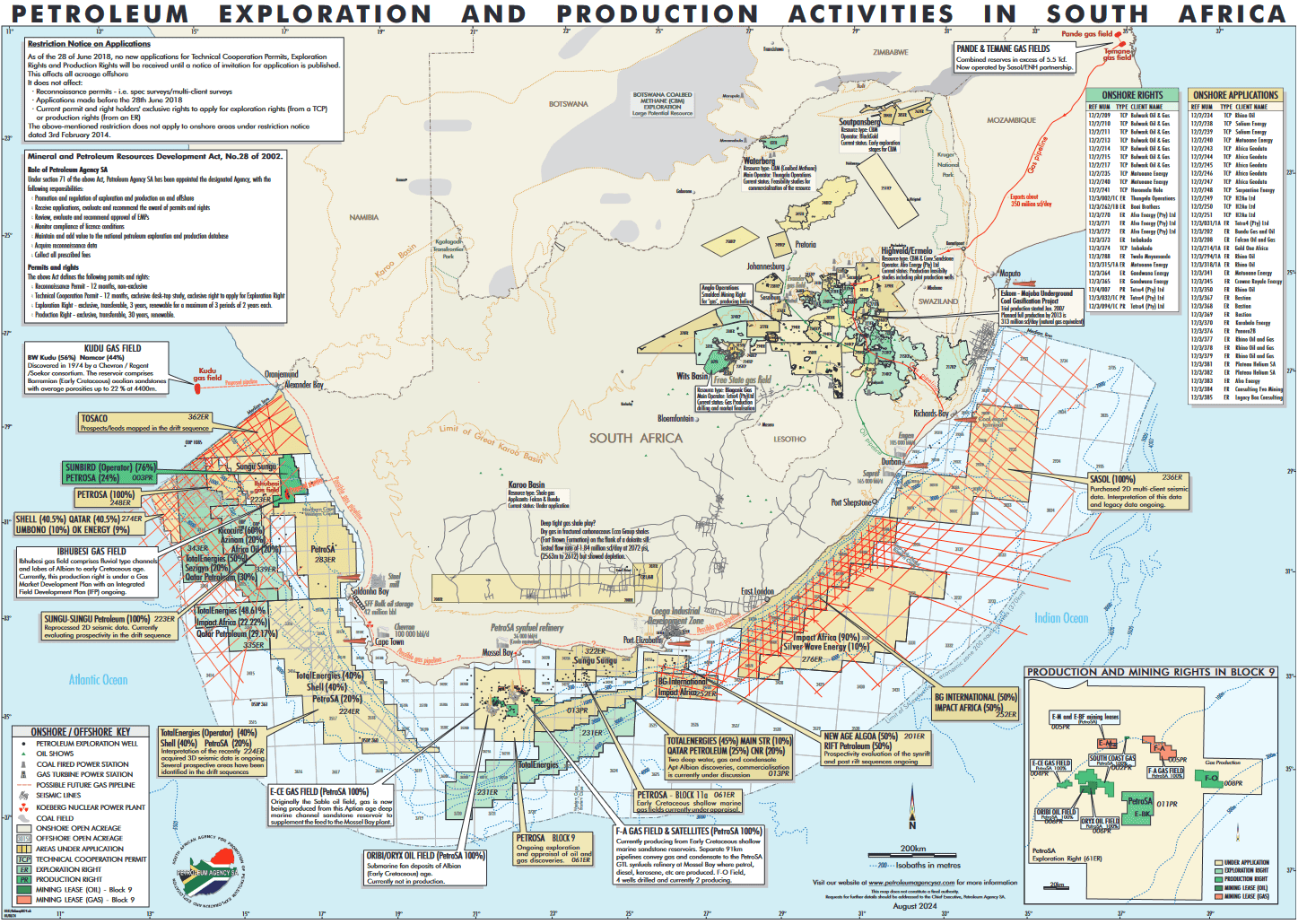

Geologically speaking, South Africa’s onshore gas bearing geology (excluding shale gas) is considered unique and generally described as compartmentalised shallow gassy sandstone originating from the deeper coal seams. Unlike shale gas, to develop and produce this shallow onshore gas, hydraulic fracturing (fraccing) is not required. Because this gas-bearing geology is ubiquitous and regionally consistent, companies like Bastion Oil and Gas South Africa, Bulwark Oil and Gas RSA and others have similarly followed the Kinetiko model. In 2024, an Australian company, D3 Energy listed on the ASX and raised initial funding of R100 million (AUS$10 million) in equity funding for further onshore gas (CBM and helium) exploration in South Africa. The results of their drilling and flow testing programme during 2024 have been extremely positive. A cursory look at the Petroleum Agency SA’s (PASA) December 2024 hub map sets out all the companies that have applied for and/or been granted petroleum rights in respect of South Africa’s onshore gas potential.

South Africa requires affordable energy and base load power

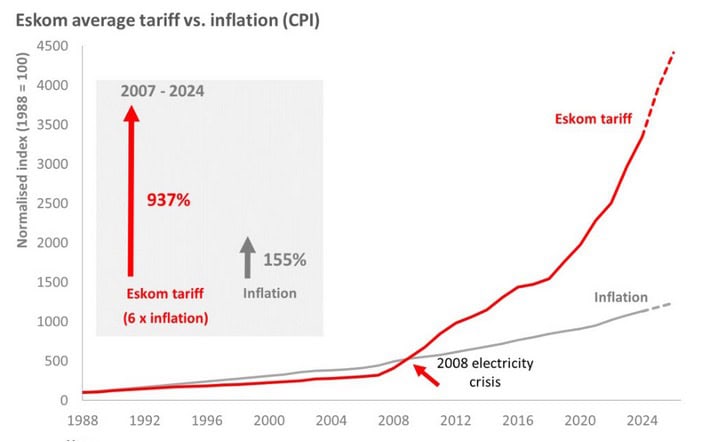

The potential for South Africa’s onshore gas to become, not only a solution for South Africa’s energy (not simply an electricity) crisis, but also providing South Africa with energy security, has largely been ignored in most energy planning modelling in favour of alternative and expensive energy solutions. It is common cause that South Africa must recognise and appreciate that, for our country to achieve inclusive growth, it requires, not only affordable electricity, but also affordable resources from which energy can be generated. Policy failures, together with numerous accounts of corruption, has led to electricity tariff increases of 937%, while inflation increased by 155% for the period 2007-2024, as reported in the August 2024 article by Power Optimal (https://poweroptimal.com/2024-update-eskom-tariff-increases-vs-inflation-since-1988-with-projections-to-2026/). Further annual Eskom electricity tariff increases are expected for 2025, with an increase of 36.1% proposed.

Against the aforesaid backdrop, the energy sector in South Africa has been caught up in a just energy transition (JET) policy framework that South Africa, at this stage, simply cannot afford. Simple and obvious solutions to the energy crisis have been overlooked in favour of a green agenda, without the necessary and costly electricity transmission infrastructure being in place. Poor planning has stymied many a proposed project that relies heavily on state-provided infrastructure; caught up in administrative red tape (and green tape), requiring financing and guarantees that the country’s balance sheet seemingly cannot justify.

It appears that foreign funding and loans in support of South Africa’s JET has had little direct positive impact on the livelihoods of South African citizens. It would seem as though the goals of energy security, affordable energy and cheap electricity have been set aside in favour of renewables as the chosen, albeit ill-advised, path to energy security and environmental sustainability. This foolhardy path necessitates the burden of higher electricity costs being socialised at the expense of South African citizens and, consistently, leading to below-expectation GDP growth.

Often lost in the translation is the fact that South Africa does not have an electricity crisis exclusively. It has an energy crisis firstly. This crisis is no more apparent than with the depletion of gas from Sasol’s Pande and Temane gas fields in Mozambique that is piped to Sasol in Secunda and then, on to industrial gas users along the Lilly pipeline, all the way to Richards Bay. Industrial gas users have been put on notice that Sasol will be unable to supply demand and that such gas supply will be reduced from 2026 until a planned dead stop in December 2027.

Numerous reports suggest that the situation in South Africa is exacerbated by the lack of state investment to maintain and expand water, transportation and communications infrastructure. Reasons therefore, as postulated in an article by Investec Bank and many other economists, include the lack of policy coordination across ministerial portfolios; corruption; poor management; the lack of maintenance capital expenditure (capex), and inertia in new capacity planning, let alone delivery of even the best laid plans. It is not surprising that, as the consequences of years of bad energy policies and decision making materialize, the default position is the use of more imported already-refined fossil fuels, and the continued use of coal for power generation. It now appears as though South Africa is looking at liquefied natural gas (LNG) importation as a potential saviour; justified by the already-high cost of energy, in general, and electricity, increasingly; if the ambition of using renewables and battery energy storage systems for baseload power becomes a reality without constraint. The recent Eskom RFP (Tender ID: 90345) for the supply of LNG to Ankerlig and Gourikwa power stations bears testimony to this. South Africa, as a buyer and price-taker will have to compete within a growing market demanding more LNG as an energy transition and energy addition fuel. It is my opinion that without a cohesive and pro-active pro-gas policy framework, a secure financing structure that mitigates political risk, blended together with international skill and experience, there is little hope of realising a fully functional South African LNG importation facility becoming operational in the next 5 to 10 years.

The 2019 integrated resource plan (IRP, draft update released in January 2024) estimates that South Africa requires an additional 30 Gigawatts (GW) of baseload electricity by 2030. The aforesaid fails to account for the needs of industries which are dependent on gas, besides those who are dependent on refined petroleum products and/or coal, but will also need to transition due to domestic and foreign market carbon taxes. South Africa consumes approximately 25 million litres of diesel, petrol, LPG and jet fuel per year; remaining an importer thereof. All these imports must be paid in hard currency with the ZAR consistently depreciating against the US$ by 6,7% compounded over the last 10 years.

Cognizance must also be taken of technological advancements in the development of cost-effective small-scale liquefied natural gas (ssLNG) processing, storage and transportation, including the potential for LNG to be used in South Africa’s trucking and other transportation modes. A recent article published by TrucksDekho in June 2024, comparing medium and heavy commercial trucks using diesel versus LNG trucks for long range transportation, concluded that, not only is LNG cheaper as a measured unit of energy; but, although the initial cost of the trucks are 22% more expensive, running costs are 40% lower, thus reducing the total cost of ownership (TCO) by 32%, with the added benefits of reduced emissions; longer range; longer service intervals; and longer life-expectancy.

All the above leads to the question: Why is South Africa not sufficiently focused on domestic gas exploration and production – onshore gas in particular – when international petroleum experts and independent resource verifiers have certified South Africa’s onshore conventional gas resource potential (incl. prospective and contingent resources) as being in excess of 20 TCF, with significant opportunities for further onshore gas discoveries?

What must be done to advance South Africa’s energy security?

Below are a few practical proposals to advance South Africa’s gas sector.

- It is time for South African investors, including banks, development finance institutions, private equity funds, pension funds and re-/insurers to take calculated risks by recognizing that onshore gas exploration risk has already been sufficiently mitigated by exploration companies. We are now entering the appraisal and development phase. Relying on government to solve our energy crisis, exclusively, is not the most viable and efficient path to achieve energy security and inspire investor confidence.

- South Africa must accelerate onshore gas exploration by providing local and international oil and gas companies with a stable and adequately certain legislative environment that has been realistically modelled to encourage and protect the investment of capital into gas exploration and production projects. Investment capital must be primarily directed at what is happening sub-surface and not above the surface.

- Oil and gas exploration in South Africa must be incentivised, particularly deep water exploration that requires significantly more capital with a much greater risk of failure. South Africa cannot afford to have major oil and gas companies leaving and/or reducing their exploration capital exposure to South Africa.

- Foreign-funded anti-fossil fuel lobbies must not be given the opportunity to abuse our courts to stymie oil and gas exploration and production, besides utilisation. PASA, the RSA petroleum licensing authority, must drive the government and the legislature to put firm pro-fossil fuel policies in place that our courts can easily and clearly interpret when dealing with the anti-fossil fuel “lawfare” being waged before them.

- Our legislation must be reviewed and amended by experts who understand the oil and gas industry. The Upstream Petroleum Resources Development Act 23 of 2024, yet to become effective, fails to address many industry concerns that were raised during the drafting and public consultation processes. An example of the unintended consequences of poor legislative drafting is Section 43 of NEMA which automatically suspends environmental authorisations upon the mere filing of an appeal notice; even if such an appeal is malicious and/or vexatious in order to abuse our judicial system as a weapon by the anti-fossil fuel lobby to delay or suspend energy-related projects, often undermining investor confidence.

- Expedited processes for the multitude of regulatory consents and approvals, besides other permitting, must be introduced as and when the national interest is at risk, over the short- to long-term, due to the full energy mix not being available for each to play their respective and combined roles. Energy security and affordability (energy access) are primary national interests and, therefore, relevant “red tape” and “green tape” must be removed post-haste.

- South Africa must follow the example of countries on our continent and elsewhere which have successfully grown their oil and gas industries by attracting investment from international oil companies. It is not difficult to understand why over the last 5 years, countries like Namibia, Guyana and now, Rwanda have been successful in attracting oil and gas exploration investment and why South Africa is failing.

- PASA must be transformed into an efficient and fully accountable independent regulator, such as NERSA, that vigorously pursues its legislative mandate, without fear or favour. As a subsidiary of the CEF, conflicts of interest within the group are, in my opinion and experience, unavoidable as CEF actively competes with the private sector.

- Lastly, experienced, competent and beyond-reproach persons with international experience must be appointed to positions of authority that have legislative control and decision-making authority over all energy-related projects, if South Africa is to benefit from its onshore and offshore gas potential. A step in the right direction is that the Minister of Electricity and Energy is now empowered, by the 2024 amendments to the Electricity Regulation Act, to issue a s34 ministerial determinations for, not only the new generation capacity to be procured, but also to procure the inter-related or inter-connected infrastructure, including gas infrastructure however, this does not assist with primary oil and gas resource exploration and production.

As Bastion continues to de-risk its onshore gas opportunities through intelligent exploration, we look forward to partnering with like-minded companies, development finance institutions and industry as joint venture partners, financiers, contractors and gas off-takers who like us consider this a worthwhile endeavour.

For more information please contact the undersigned at barrisford@bastionoil.com or info@bulwarkoil.co.za

Barrisford Petersen

Founder and Managing Director

Bastion Oil and Gas South Africa (Pty) Ltd

Bulwark Oil And Gas SA (Pty) Ltd

Rockit Energy (Pty) Ltd

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE RESTRICTED BY LAW. ACCORDINGLY, THIS DOCUMENT MAY NOT BE DISTRIBUTED IN ANY JURISDICTION EXCEPT IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE LEGAL REQUIREMENTS APPLICABLE TO SUCH JURISDICTION. IN PARTICULAR, YOU MAY NOT DISTRIBUTE, FORWARD, REPRODUCE, TRANSMIT OR OTHERWISE MAKE AVAILABLE THIS DOCUMENT OR DISCLOSE ANY INFORMATION CONTAINED IN IT OR CONVEYED DURING ANY ACCOMPANYING ORAL PRESENTATION (THE “INFORMATION”), IN WHOLE OR IN PART, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE TO DO SO WOULD BE UNLAWFUL. FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THESE RESTRICTIONS MAY CONSTITUTE A VIOLATION OF APPLICABLE SECURITIES LAWS. PERSONS INTO WHOSE POSSESSION THIS DOCUMENT COMES ARE REQUIRED BY THE COMPANY TO INFORM THEMSELVES ABOUT AND TO OBSERVE ANY SUCH RESTRICTIONS. NEITHER BASTION OIL AND GAS SOUTH AFRICA (PTY) LTD (INCLUDING ITS AFFILIATE BULWARK OIL AND GAS SA) (“COMPANY”) NOR ITS DIRECTORS, OFFICERS, EMPLOYEES, RESPECTIVE AFFILIATES, AGENTS OR ADVISERS ACCEPT ANY LIABILITY TO ANY PERSON IN RELATION TO THE DISTRIBUTION OR POSSESSION OF THIS DOCUMENT IN OR FROM ANY JURISDICTION.

The Document and the Information have been prepared by or on behalf of and is the sole property of the Company. The Information is being provided to you is not a complete record. The Information does not purport to be full or complete and does not constitute investment advice. No representation or warranty, express or implied, is given by or on behalf of the Company, its affiliates, agents or advisers or any other person as to, and no reliance may be placed for any purposes whatsoever on, the adequacy, accuracy, completeness, fairness or reasonableness of the Information. None of the information has been independently verified by the Company, its affiliates, agents or advisers or any other person, and no liability or responsibility whatsoever is accepted by any of them for any loss howsoever arising, directly or indirectly, from any use of the Information or otherwise arising in connection therewith. The Company, its affiliates, agents and advisers do not undertake and are not under any duty to update this Document or to correct any inaccuracies in the Information which may become apparent or to provide you with any additional information.

The sole purpose of this Document is to provide background information to assist you in obtaining a general understanding of the business of the Company. This Document does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or subscribe for, securities of the Company in any jurisdiction. It is not intended to provide the basis of any investment decision, financing or any other evaluation and is not to be considered as a recommendation by the Company, its affiliates, agents or advisers that any recipient of this Document purchase or subscribe for any securities in the Company. Each recipient of this Document contemplating any investment in the Company is required to make and will be deemed to have made its own independent investigation and appraisal of the business, results of operations, financial condition, liquidity, performance and prospects of the Company and the merits and risks of an investment in the securities of the Company. The delivery of this Document at any time does not imply that the information in it is correct as of any time after its date, or that there has been no change in the business, results of operations, financial condition, liquidity, performance and prospects of the Company since that date and no obligations is accepted to update any such information after the date of the Document. No person affiliated with the Company, their directors, officers, employees, respective affiliates, agents or advisers has been authorised to give any information or to make any representation not contained in this Document and, if given or made, such information or representation must not be relied upon. This Document may contain forward-looking statements, including, but not limited to, statements as to the Company’s business, results of operations, financial condition, liquidity, performance and prospects and trends and developments in the markets in which the Company operates. Forward-looking statements include all statements other than statements of historical fact and in some cases may be identified by terms such as “targets”, “believes”, “expects”, “anticipates”, “estimates”, “aims”, “intends”, “will”, “may”, “would”, “could” or, in each case, their negative or comparable terms. By their nature, forward-looking statements involve risk and uncertainty because they relate to future events and circumstances that may or may not occur. Several factors, which may be beyond the control of the Company, its affiliates, agents and advisers, could cause actual results and developments to differ materially from those expressed or implied by the forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements in this document reflect the Company’s view with respect to future events as at the date hereof and are subject to known and unknown risks, uncertainties and assumptions relating to the Company’s operations, results of operations, financial condition, growth, strategy, liquidity and the markets in which the Company operates. No assurances can be given that the forward-looking statements in this Document will be realised. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance. The Company, its affiliates, agents and advisers undertake no obligation and do not intend to update any forward-looking statements in this Document to reflect events or circumstances after the date of this Document.

Recent Comments